If you work in beauty packaging, you’ve seen the narrative: plastic = bad, therefore the only responsible move is to “go plastic‑free.” That storyline is emotionally satisfying—and operationally risky.

Because in the real world, most packaging sustainability failures happen after the resin choice, when design decisions quietly make a pack unsortable, unreprocessable, or unmarketable as recycled material. The material isn’t automatically “the villain.” The villain is packaging that can’t move through collection, sorting, and reprocessing systems at scale.

This is why the most practical sustainability upgrade for cosmetics brands isn’t always switching to glass or aluminum. Often it’s a design-for-recycling (DfR) retrofit: simplifying structures, reducing incompatible components, enabling detection at MRFs, and making end‑markets more likely—while still delivering a premium look, product protection, and great dispensing.

The packaging industry already has robust guidance for how to do this. The Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) defines recyclability as a system outcome, requiring not only design, but also access, acceptance, and markets. In other words: even a “good” polymer can fail if the pack is designed in a way that breaks sorting or contaminates the recycling stream. Source

And Europe’s RecyClass similarly treats recyclability as a component‑level compatibility question, using a traffic‑light logic—green (preferred), yellow (limited compatibility), red (detrimental). Source

So if your sustainability messaging (or procurement specs) still start and end with “avoid plastic,” this article is your reset: Plastic packaging isn’t the villain—bad design is.

Why this matters now (global, not theoretical)

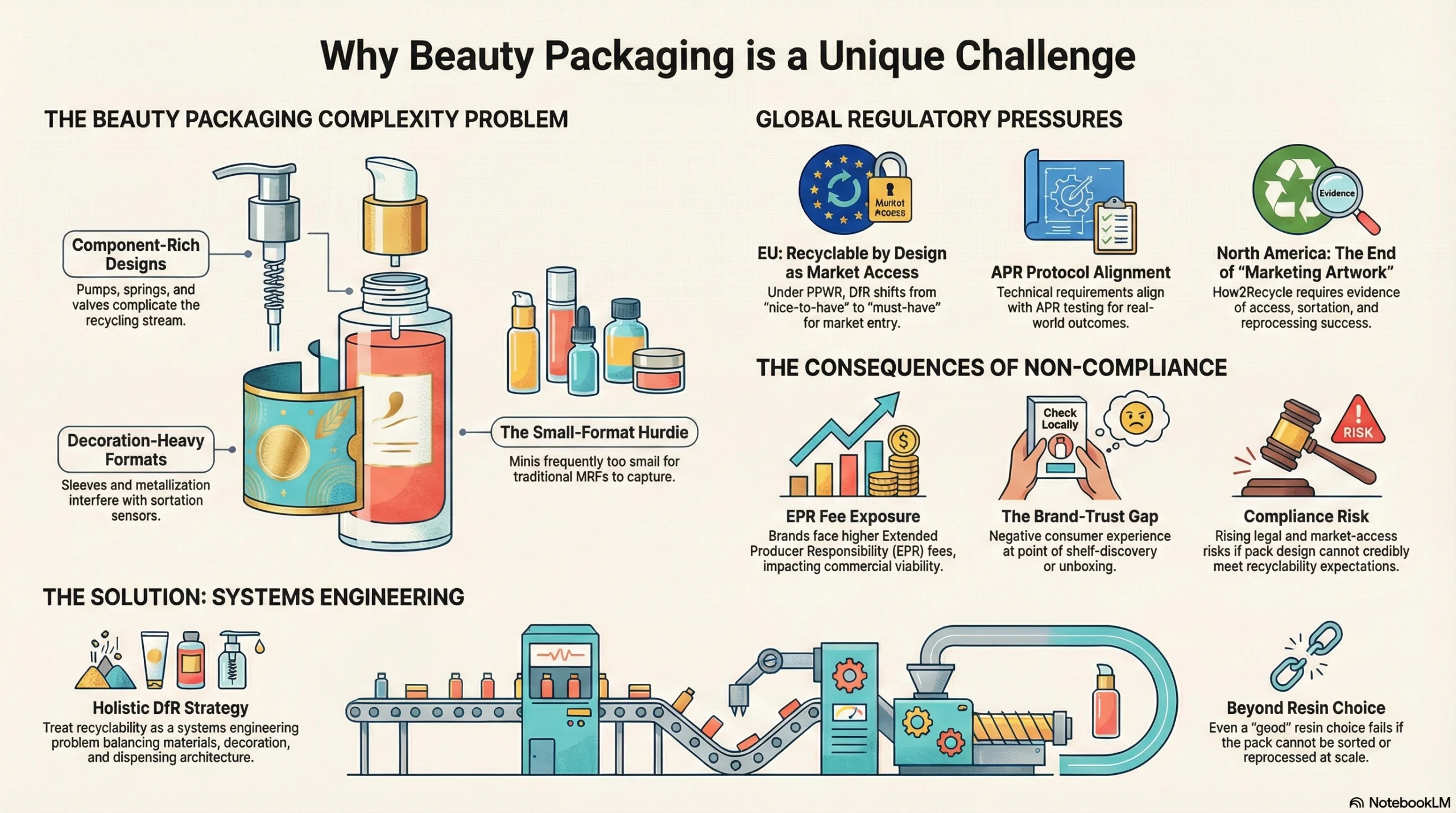

Two forces are converging—and they hit cosmetics packaging harder than most categories because our packs are decoration-heavy (sleeves, metallization), component-rich (pumps, springs, valves), and often small-format (minis, travel sizes):

“Recyclable by design” is becoming a market-access requirement—especially in the EU

In the EU, the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) is part of a broader push to reduce packaging waste and drive more sustainable packaging systems. For global beauty brands selling into Europe, the practical implication is that DfR is shifting from “nice-to-have” to “must-have”: if the pack design can’t credibly meet recyclability expectations, the brand’s compliance risk rises, and the SKU becomes harder to defend commercially. This is exactly why our internal guidance should treat recyclability as a systems engineering problem (materials + decoration + dispensing architecture), not a single material decision.

Recycling claims are being policed—especially in North America

In the US/Canada, recycling labels are no longer “marketing artwork.” How2Recycle’s guidelines have evolved quickly in response to legislation and the program’s technical requirements (including alignment with APR testing/protocols). The outcome is that some packaging formats are being downgraded, and “recyclable” claims are increasingly difficult to support without evidence of access, sortation, and reprocessing success.

For cosmetics brands, this matters because a pack that looks sustainable can still be labeled “check locally” or “not yet recyclable” if real-world systems can’t reliably handle it—creating a brand-trust gap right at shelf and unboxing.

Bottom line for global cosmetics brands

Your packaging design choices now directly influence compliance risk, EPR fee exposure, label eligibility, and consumer trust—not just aesthetics. If a pack can’t be sorted or reprocessed at scale, the sustainability story collapses, even if the resin choice is “good.” (This is why the rest of this article focuses on design-for-recycling, mono-material systems, PCR realities, and refill UX—the levers that actually change outcomes.)

What “bad design” actually means in recycling terms

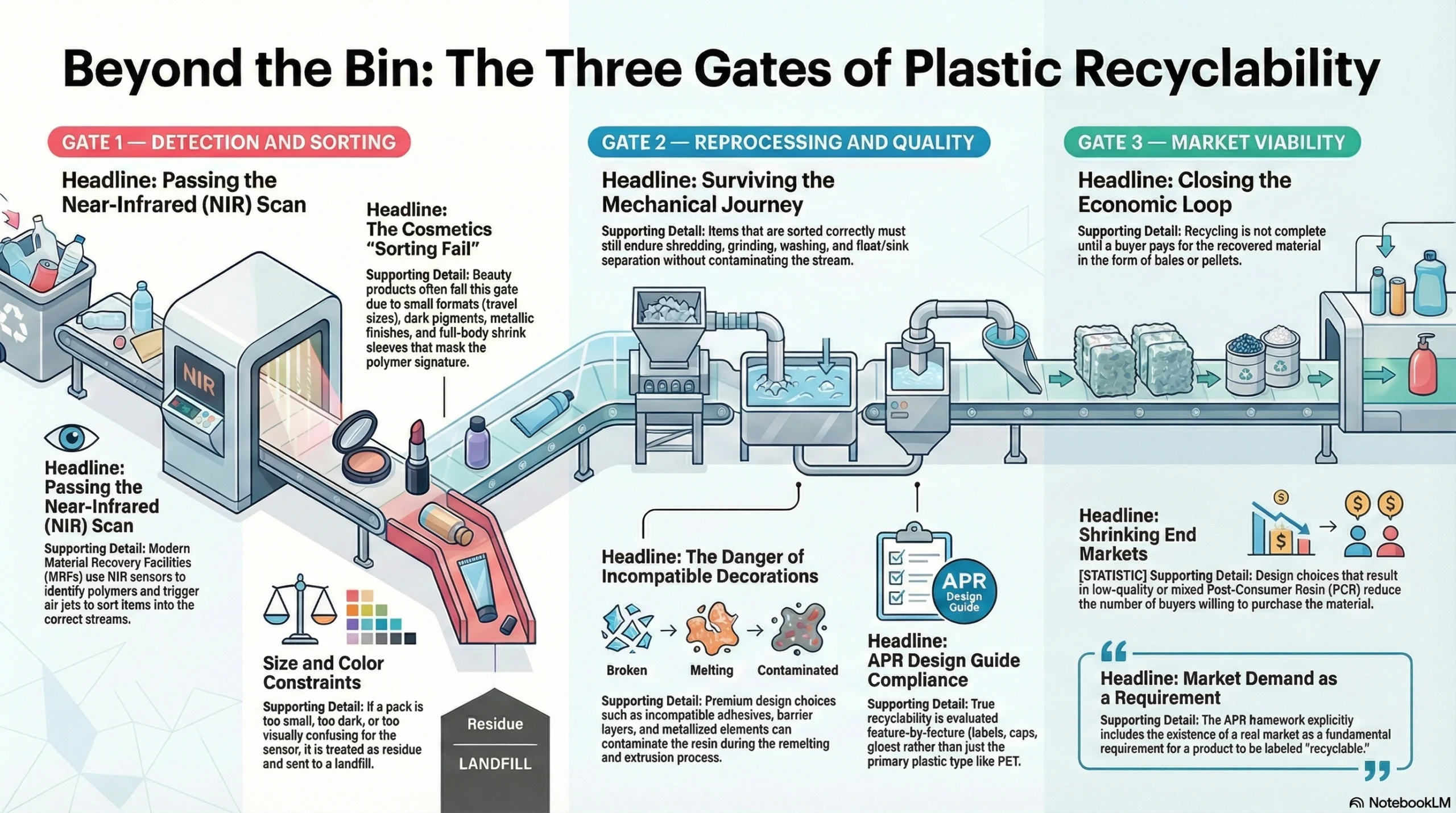

Most people imagine recycling as a simple bin decision: Did the consumer recycle it or not? But recycling is an engineered chain with hard physical constraints. The pack must pass three practical gates:

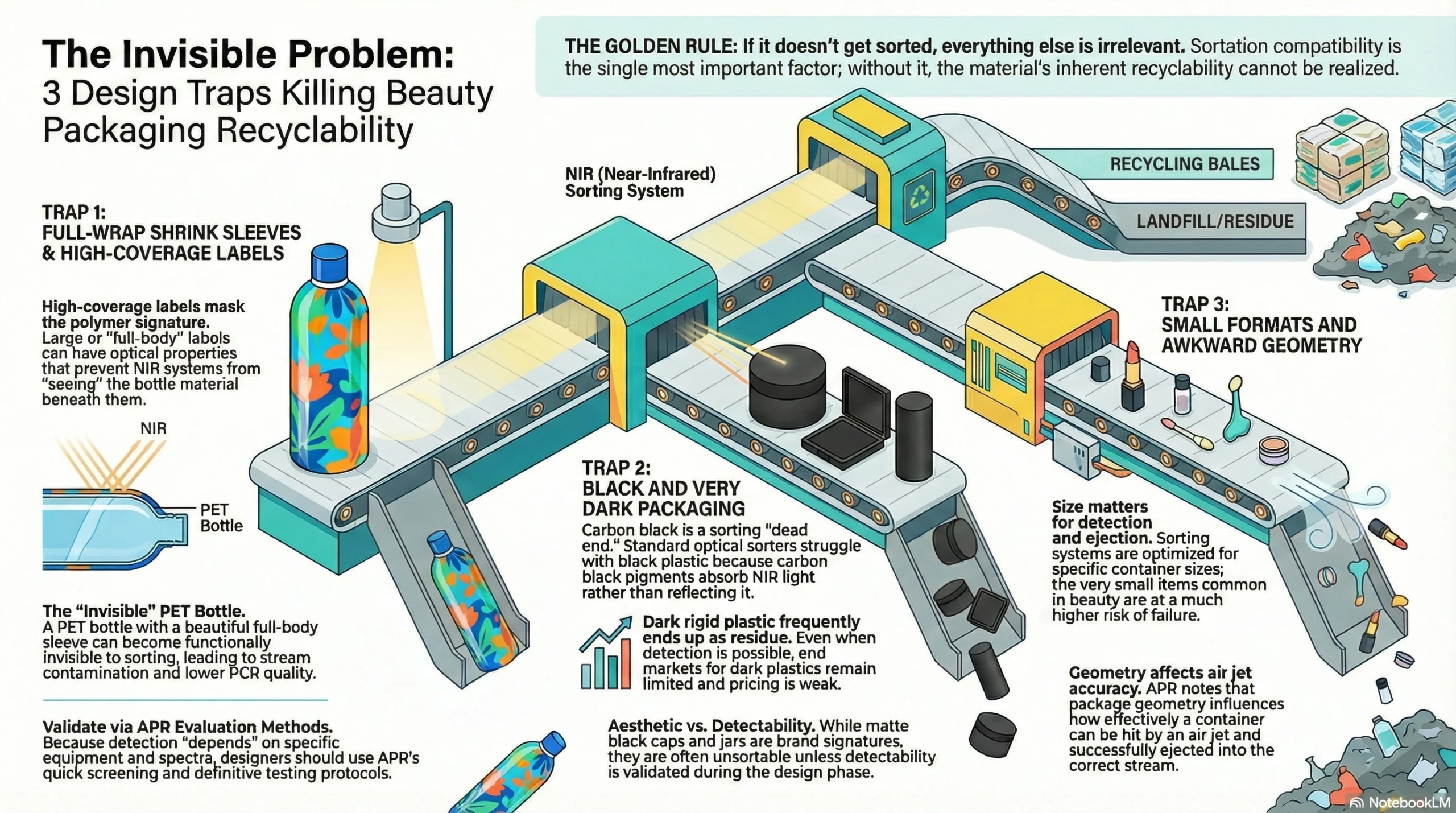

Gate 1 — Can the pack be detected and sorted at a MRF?

Modern facilities often rely on near‑infrared (NIR) sorting to identify polymers and blow the right items into the right streams using air jets. If your packaging’s polymer signature is masked—or the pack is too small, too dark, or too confusing—your “recyclable plastic” effectively becomes residue. Source

Cosmetics packaging gets hit here because beauty loves:

- full-body decoration

- metallic finishes

- shrink sleeves

- dark pigments

- small formats (travel sizes, minis, lip products)

All of which can interfere with detection or handling.

Gate 2 — Can it be reprocessed into clean, usable PCR?

Even if it’s sorted correctly, the pack still needs to survive:

- shredding / grinding

- washing

- separation steps (including float/sink dynamics)

- remelting / extrusion

A “premium” decoration choice (wrong label, incompatible adhesive, barrier layer, metalized element) can contaminate resin and degrade PCR quality—reducing the chance of a buyer actually purchasing that recycled material. This is why the APR Design Guide evaluates packaging feature-by-feature, not just “is it PET?” Source

Gate 3 — Is there a real market for the recovered material?

Recycling is not complete until somebody pays for the bales or pellets. If the design choices lead to mixed, low‑quality, or difficult‑to‑use PCR, end markets shrink. The APR framework explicitly includes markets as a requirement for recyclability—not an afterthought. Source

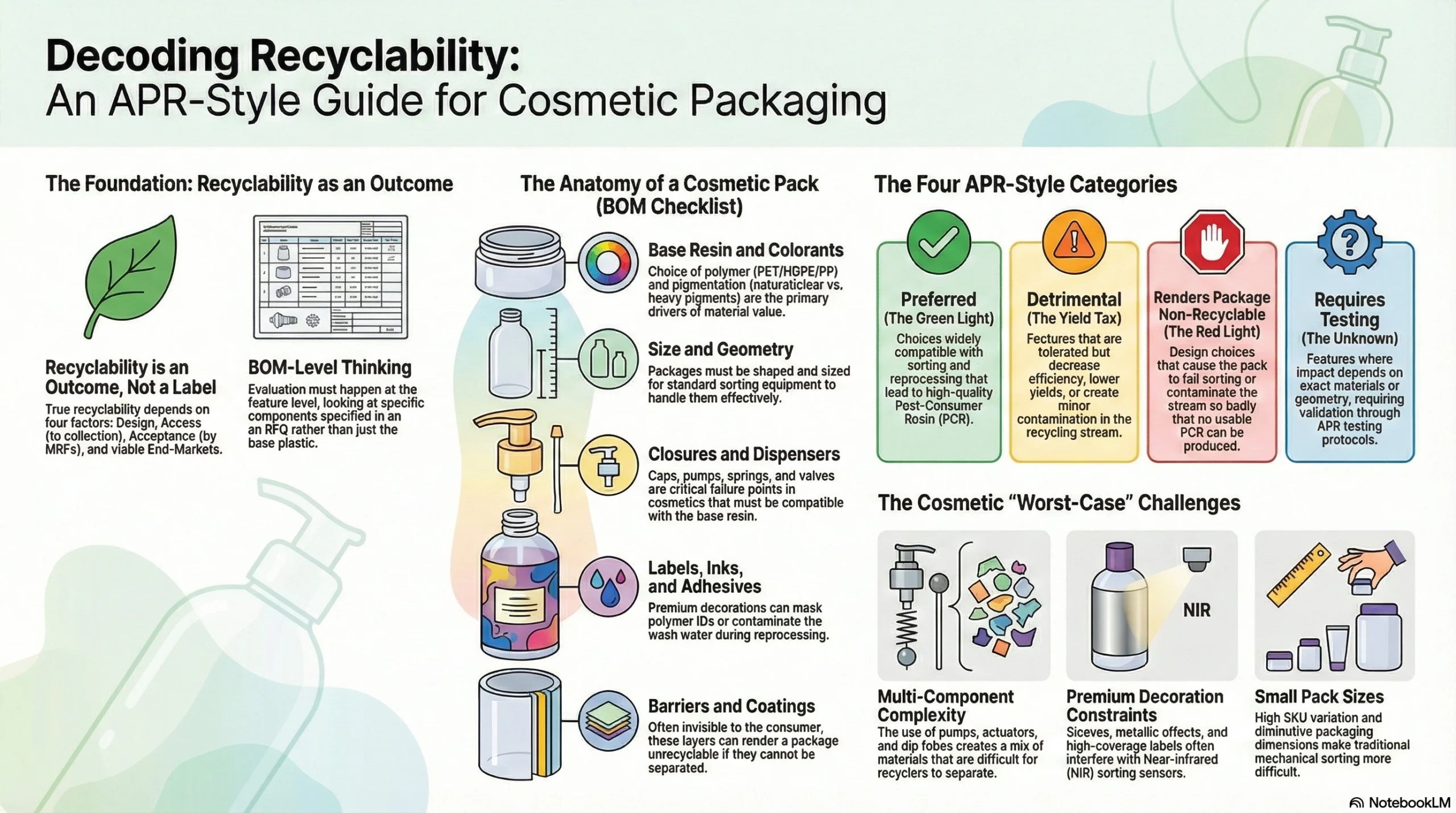

Design‑for‑Recycling (DfR) isn’t a vibe—it’s an engineering spec

When a cosmetics brand says “make it recyclable,” the real question isn’t which material sounds good in a sustainability deck—it’s whether the entire pack architecture can survive the real recycling chain: MRF detection → correct polymer stream → washing/separation → reprocessing → saleable PCR. DfR is therefore an engineering spec: it defines what your bottle, cap, pump, label, inks, adhesives, and any barrier layers are allowed to be—so the pack can be sorted and processed at scale. That’s exactly why APR and RecyClass are so useful: they convert “sustainability” into design rules and testable requirements, not vibes.

How APR thinks: feature‑level recyclability categories (why this fits cosmetics)

APR’s core insight is that recyclability is not a label you print—it’s an outcome. APR defines recyclability as dependent on four conditions: Design, plus Access, Acceptance, and Markets. This is the part that stops teams from saying “it’s PET, therefore recyclable.” A PET bottle with the wrong sleeve, adhesive, color, closure, or dispensing system can still fail at sorting or contaminate the stream—so APR evaluates the pack by the features that actually determine whether recyclers can handle it. Source

What “feature‑level” means in practice (BOM-level thinking)

APR breaks packaging down into the things packaging engineers actually spec in an RFQ, such as:

- Base resin (e.g., PET vs HDPE vs PP)

- Colorants (e.g., natural/clear vs heavily pigmented)

- Size & geometry (what sorting equipment is optimized to handle)

- Closures/dispensers (caps, pumps, springs, valves—critical in cosmetics)

- Labels / inks / adhesives (often where premium decoration creates recycling failures)

- Barrier layers / coatings / attachments (often “invisible” to marketing but huge to recyclers)

APR explicitly frames these as design features that drive whole-package recyclability outcomes.

The four APR-style categories—what they mean for a cosmetics pack

APR’s design guidance uses categories like Preferred, Detrimental, Renders Package Non‑Recyclable, and Requires Testing (or “unknown until tested”), so teams can classify each feature and then see what the whole pack becomes.

Preferred (good for recycling): a design choice that’s widely compatible with how MRFs sort and how reclaimers wash and reprocess, leading to higher-quality PCR. In cosmetics, “preferred” often looks like simple, compatible structures and decoration choices that don’t mask polymer ID or contaminate regrind.

Detrimental (tolerated but hurts yield/quality): the pack may still be processed, but you are “taxing” the system—lower yields, more residue, more contamination risk, poorer PCR quality. In cosmetics, many premium cues fall here: certain high-coverage labels, complex multi-part dispensing systems, and non-ideal color strategies can degrade outcomes even if the bottle resin is “right.”

Renders Package Non‑Recyclable: a design choice that causes the pack to fail sorting or reprocessing so badly that recyclers can’t effectively produce usable PCR from it. For example, if the pack is designed so it cannot be reliably detected/sorted (or creates severe contamination), the resin choice becomes irrelevant.

Requires Testing: the feature’s impact depends on the exact materials, geometry, or decoration—so APR expects you to validate via testing protocols rather than guessing. This is especially common in cosmetics because decoration and dispensing systems vary dramatically between SKUs.

Why APR’s method is powerful specifically for cosmetics

Cosmetics packaging is a “worst-case” category for recycling because it combines:

- multi-component function (pumps, actuators, springs, dip tubes)

- premium decoration (sleeves, coatings, metallic effects)

- high SKU variation and small pack sizes

APR’s feature-level approach turns that complexity into a structured decision path: we can’t fix everything at once, so which features are causing the failure? That makes recyclability improvement a design optimization project, not a brand argument.

Bonus specificity: APR + the “sorting reality” link (NIR is a design constraint)

APR also publishes guidance showing how sorting works (notably NIR sorting) and which design choices interfere—like high-coverage labels and dark/black colors. This is why APR-style DfR specs often start with “will the sorter see the polymer?” before you even get into reprocessing.

How RecyClass thinks: compatibility by stream (traffic-light logic)

If APR is the “engineering spec” mindset commonly referenced in North America, RecyClass is the “compatibility by recycling stream” mindset widely used in Europe. The logic is straightforward and highly usable for global brands:

RecyClass uses a traffic-light system

RecyClass evaluates packaging features/components for a given recycling stream using:

- Green = full compatibility

- Yellow = limited compatibility

- Red = non-compatibility / detrimental

That makes it easy to communicate across teams (marketing, design, procurement, engineering): “this feature is red—avoid unless we redesign.” Source

Why RecyClass is “living guidance” (and why that matters)

A critical detail is that RecyClass updates guidance based on:

- Testing Campaigns

- Technology Approvals

- and where needed, Recyclability Evaluation Protocols for features not yet covered

This matters because recycling is not static. Sorting technology, wash processes, and accepted formats evolve. A design that was borderline five years ago may become acceptable—or it may be reclassified as problematic if real-world testing shows contamination or poor yields. This is why relying on old assumptions (“sleeves are fine,” “dark colors are fine,” “it’s technically recyclable”) becomes risky for global brands. Source

The silent recyclability killer in beauty: NIR sortation interference

If you only fix one thing this year, fix sortation compatibility. Because if your pack doesn’t get sorted correctly, everything else is irrelevant.

APR’s NIR guidance highlights several design traps that commonly appear in cosmetics:

Trap 1: Full-wrap shrink sleeves and high-coverage labels

High coverage labels—especially those with optical properties that mask the container—can prevent NIR systems from seeing the polymer signature of the bottle. APR provides evaluation methods (including quick screening and definitive testing protocols) because “it depends” on real spectra and equipment. Source

Practical cosmetic translation:

A PET bottle with a beautiful full-body sleeve can become functionally “invisible” to sorting. If it goes into the wrong stream, it can contaminate a bale, increasing cost and lowering PCR quality. That’s not a plastic problem—that’s a design problem.

Trap 2: Black and very dark packaging

Standard optical sorters often struggle with black plastic due to carbon black pigments absorbing NIR. Industry reporting shows black rigid plastic is frequently unsortable and often ends up as residue; even when detection improves, end markets remain limited and pricing is weak. Source

APR’s NIR guidance also flags dark/black as a key risk for detection. Source

Practical cosmetic translation:

That matte black cap, actuator, or jar might be a brand signature—but it can also be a sorting dead end unless you validate detectability and end-market realities.

Trap 3: Small formats and awkward geometry

APR notes that package size and geometry influence detection and correct ejection by air jets. Sorting systems are optimized for certain container sizes; very small items (common in beauty) are at higher risk.

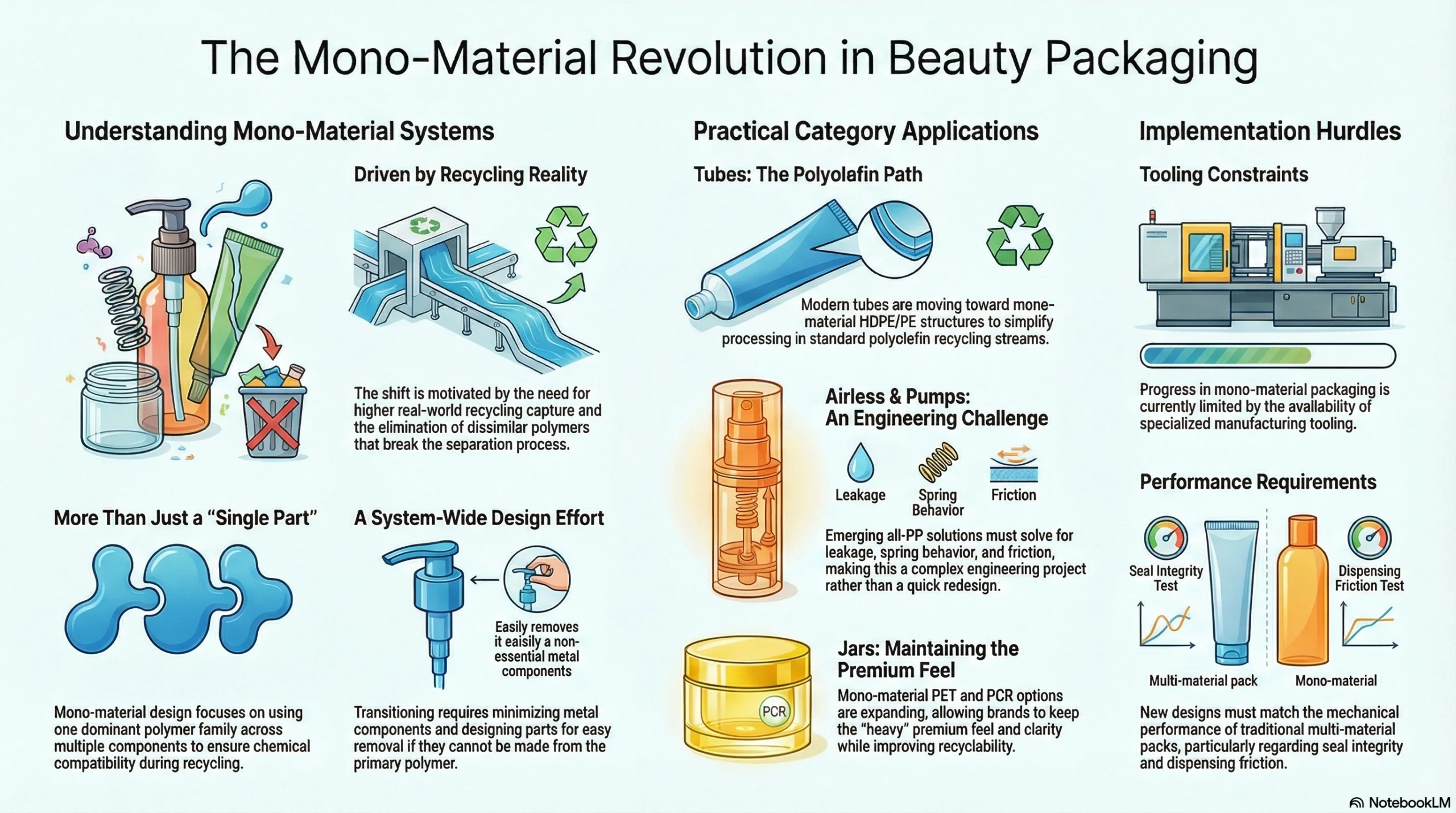

Mono-material packaging: what “mono” actually means

“Mono-material” has become a buzzword, but for recyclers it means something concrete: the system is dominated by one polymer family so it can move through sorting and reprocessing with fewer contamination issues.

Beauty Packaging reports the push toward mono-materials is partly driven by low real-world recycling capture and rising consumer pressure, and it highlights mono-material progress in tubes, pumps, jars, and airless packs—while also noting tooling availability constraints. Source

Mono-material isn’t always “one part”

Cosmetics dispensing often requires multiple components. The mono-material strategy is usually:

- one dominant polymer family (e.g., PP system or PE/HDPE system)

- avoid dissimilar polymers that break separation

- minimize metal where it causes problems

- design for easy removal where separation is necessary

This is why mono-material is a system design effort, not a “swap the bottle resin” task.

Where mono-material works well in cosmetics (practical categories)

- Tubes: moving toward mono-material HDPE/PE structures simplifies recycling in polyolefin streams (where accepted). Source

- Airless & pumps: emerging all‑PP solutions show feasibility, but performance requirements (leakage, spring behavior, friction) make this a true engineering project, not a quick redesign. Source

- Jars: mono-material PET jars and PCR options are expanding, helping maintain clarity and premium feel while improving recyclability pathways. Source

PCR plastic in cosmetics: the real problem is “can consumers accept it?”

PCR is one of the most important levers for circularity, but cosmetics has an unusually high aesthetic and sensory bar. That’s why PCR adoption often fails not in procurement—but at the consumer experience layer.

A 2024 study on consumer acceptance of PCR packaging with off-odor tested shampoo bottles at different PCR percentages (0/10/50/100) and found that higher PCR content reduced acceptability and willingness to buy—especially when odor pleasantness and familiarity declined. Crucially, odor attributes explained a large portion of consumer judgments. Source

What this means for beauty brands

If your PCR strategy is “use the highest percentage possible,” you may unintentionally trigger:

- consumer rejection (“it smells recycled”)

- returns and negative reviews

- pressure to add over-packaging or heavy decoration to hide defects

- or a retreat to virgin resin for premium lines

The study’s implication isn’t “don’t use PCR.” It’s: treat PCR like a material with variability and sensory risk that must be engineered. Source

PCR design strategies that don’t sabotage recyclability

In practice, PCR success in cosmetics often relies on:

- geometry choices that reduce visual defects (texture, wall thickness, matte vs gloss)

- color strategy that avoids high-risk NIR blockers while managing grayness (avoid defaulting to black unless validated) Source

- component strategy (start PCR in parts with lower sensory exposure, or in refill packs)

- testing and supplier control, because “PCR” is not one thing—feedstock and process matter

Table: PCR packaging reality vs. design response (cosmetics)

| PCR challenge in beauty | What consumers perceive | Design response (DfR-aware) | Why it works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-odor | “Smells recycled / dirty” | Treat odor as a spec; validate material lots; avoid overcompensating with non-recyclable decoration | Odor strongly predicts acceptance and willingness to buy Source |

| Grayness / color drift | “Looks cheap” | Use form/finish and controlled pigmentation without blocking NIR sortability | Dark/black can reduce NIR detection Source |

| Variability | “Inconsistent brand look” | Define acceptable visual ranges; design the pack to “own” natural PCR variation | Maintains premium feel without adding recycling-breaking layers |

Refillables: the sustainability win only happens when people actually refill

Refill systems are often described as the “future,” but refillable packaging is a behavior + logistics product, not just a container.

Beauty Packaging documents strong market momentum: refill offerings rising significantly over recent years and a growing market value for refillable packaging—while stressing that successful refill models must prioritize convenience, balanced price/function, and integrated support. Source

Case study: Dove body wash concentrate refills (why the mechanism matters)

Packaging Digest’s coverage of Dove’s reuse/refill system is valuable because it shows the real design work behind a successful refill: a quick-connect cap, clear fill instructions, QR education, and channel-specific packaging for e-commerce vs retail. This is not “just sell a refill pouch.” It’s designing a system that consumers can execute correctly every time. Source

It also gives concrete impact framing: after multiple refills, the system claims meaningful reductions in plastic use and water shipped, plus estimated GHG reductions—illustrating how refill models can outperform single-use formats when repeat behavior happens.

And Dove’s deodorant refill example shows how durable outer packs can pair with high‑PCR refills, reducing plastic while maintaining a premium, reusable shell. Source

Refill design constraints cosmetics teams underestimate

A refill pack must solve:

- leak prevention under shipping and bathroom use

- hygiene and contamination risk

- intuitive alignment (“wrong-way” prevention)

- repeatability (must work on refill #5, not just refill #1)

- end-of-life clarity (how to recycle the refill component in each market)

This is why refill can be brilliant for certain categories (fragrance, skincare, deodorant shells, certain airless formats)—and a flop in others unless UX is engineered.

Labels: your “recyclable” design can still fail if instructions are wrong

A design-for-recycling (DfR) upgrade only delivers real-world impact if the last step—consumer disposal—is correct. In cosmetics, this “last mile” is where even well-engineered packs often collapse: consumers see a bottle and assume “recycle,” but the pack may be multi-component (pump + cap + bottle), partially contaminated (product residue), or made of a format not consistently accepted in local systems.

When the on-pack message is unclear or wrong, you get two costly failure modes: (1) contamination (wish-cycling that lowers bale quality) and (2) missed capture (recyclable items thrown away because instructions are confusing). That’s why labels are not decoration—they’re a system interface between your engineered design and the infrastructure that determines the outcome.

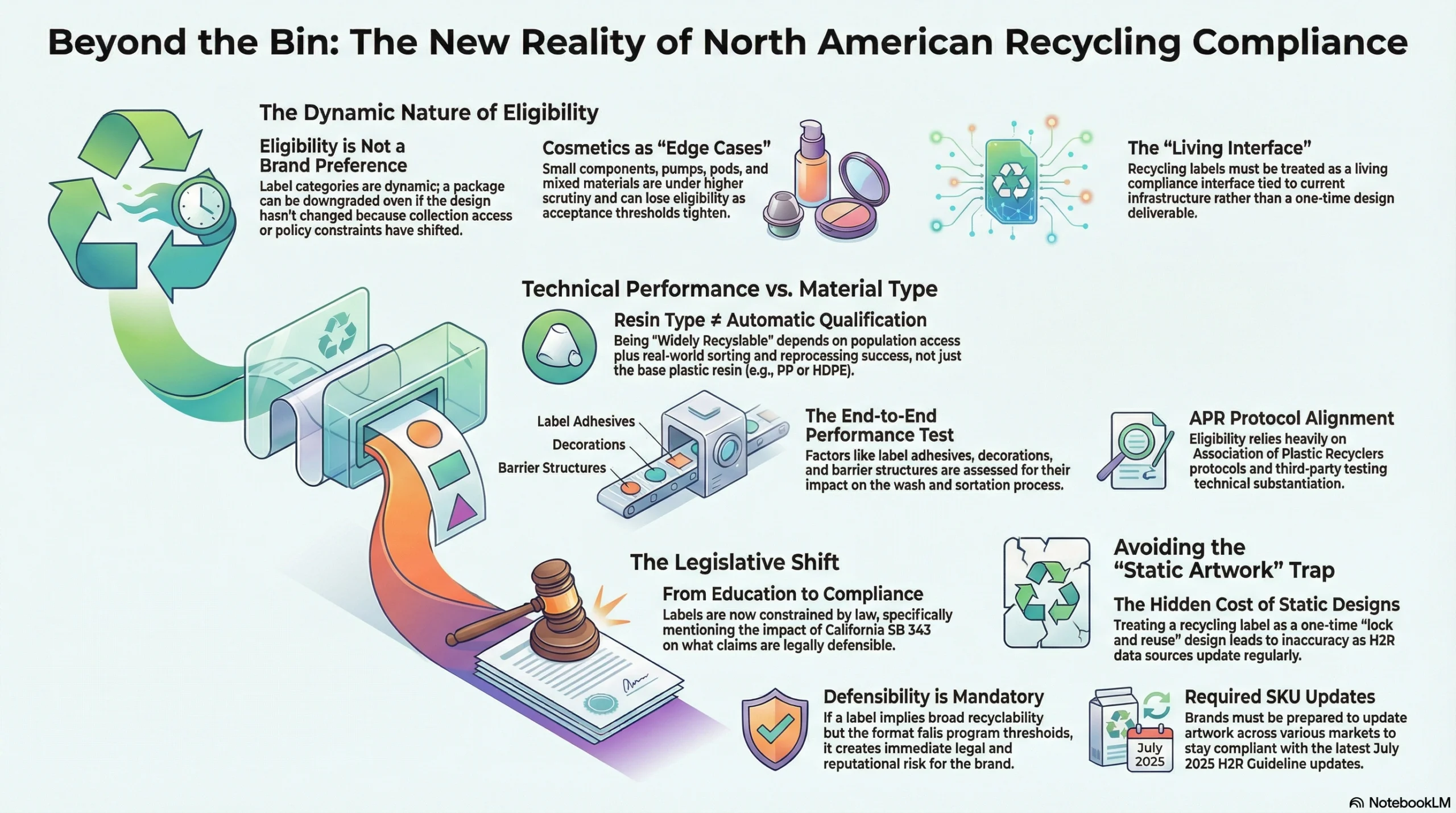

US/Canada: How2Recycle is increasingly technical (and law-driven)

1) How2Recycle label eligibility is not “brand preference”

The abbreviated How2Recycle Guidelines for Use (updates through July 31, 2025) make a point many marketing teams miss: label eligibility is dynamic. Categories and instructions change as the program updates its underlying data sources, and as laws and policy constraints shift what can be called “recyclable.” This is why formats can be downgraded even if the packaging itself hasn’t changed—because the system reality changed (collection access, sorting performance, reprocessing success, or policy requirements).

From a cosmetics perspective, this is critical because beauty packaging formats are often “edge cases”: pumps, small components, pods, mixed materials, decorative labels, and barrier structures. These are the exact types of packs that can lose eligibility if acceptance thresholds tighten or if testing shows poor performance.

2) “Widely Recyclable” depends on access and real-world sortation/reprocessing—not just resin type

How2Recycle’s “Widely Recyclable / Check Locally / Not Yet Recyclable” logic is grounded in population access plus technical performance. In other words, “it’s PP” does not automatically qualify; eligibility depends on whether the format is collected widely enough and whether it reliably sorts and reprocesses. The guidelines explicitly emphasize alignment with APR, including reliance on APR protocols and third-party testing for technical substantiation.

What this means in the real world for a cosmetics bottle:

If your bottle is HDPE but has a label/adhesive system that doesn’t behave in wash processes, or your decoration interferes with sorting, your “good resin” choice can still lead to a worse label outcome because performance is assessed end-to-end. How2Recycle points to APR testing and critical guidance protocols as the proof pathway—not marketing claims.

3) Why this is “law-driven”: claims and labels are constrained by legislation

The How2Recycle guidance highlights how legislative impacts (explicitly including California SB 343 impacts on label eligibility) shape what labels and claims are defensible. The practical lesson for Jarsking’s global customers is that recycling labels in North America have become compliance-sensitive, not just educational. If your label implies broad recyclability but the format fails the program’s thresholds or policy rules, you can create legal and reputational risk.

4) “Static artwork” is the hidden cost center

Brands often treat recycling labels like a one-time design deliverable: create artwork, lock it, and reuse it across markets and years. The How2Recycle document makes it clear why that’s risky: updates occur regularly, and eligibility can shift, which means the same SKU can require label updates over time to stay accurate.

Practical takeaway (US/Canada): For global cosmetics brands selling in the US/Canada, you can’t treat recycling labels like static artwork. They are a living compliance interface tied to infrastructure, testing, and law.

UK: OPRL is intentionally binary (and infrastructure-based)

1) OPRL is designed to reduce consumer confusion—by reflecting UK collection reality

The On-Pack Recycling Label (OPRL) scheme deliberately simplifies disposal into clear signals: “Recycle” or “Do Not Recycle,” with thresholds based on what UK local authorities actually collect and what is effectively sorted and sold as recyclate. Specifically, OPRL defines “Recycle” when 75%+ of UK local authorities collect that packaging type and it is effectively sorted and sold; “Do Not Recycle” when <50% collect; and an intermediate “Check Home Collections” status for 50–75%. This is aligned with ISO 14021 principles and is explicitly infrastructure-linked. Source

Cosmetics-specific implication: A component may be “technically recyclable” in an engineering sense (polymer compatibility), but still receive a “Do Not Recycle” instruction if UK collection coverage and end-market outcomes do not meet the scheme’s thresholds. That’s not inconsistency—it’s OPRL doing its job: preventing wish-cycling and contamination by telling the truth about UK reality.

2) OPRL recognizes multi-component packaging (critical for pumps and caps)

OPRL includes additional label types (including multi-component guidance, refill labels, and call-to-action prompts like “rinse” or “empty”) specifically because many packs are not single-material objects. This matters for cosmetics—where a bottle might be recyclable but a pump may not be, and where residue and separation steps influence outcomes. OPRL’s structure supports more accurate consumer behavior at the point of disposal.

Practical takeaway (UK): For UK SKUs, disposal guidance must reflect UK collection and reprocessing reality—not EU averages and not US assumptions.

Why labeling and design must be built together

Cosmetics packaging creates high confusion risk because it often combines:

- Multiple components (overcap + actuator + pump + bottle + dip tube)

- Product residue (lotions, serums, oils) that consumers may not rinse

- Premium decoration that makes components hard to identify (metallized looks, full sleeves)

- Small parts that consumers don’t know whether to separate

If the label doesn’t clearly tell consumers what to do—“cap on vs cap off,” “pump off,” “rinse,” “check locally”—you increase contamination and decrease capture, even after spending money to improve recyclability. This is why How2Recycle and OPRL aren’t just “nice labels.” They’re behavior design tools tied to system outcomes.

Policy pressure: why “design-for-recycling” is turning into cost and compliance (EU + US)

EU direction: PPWR is pushing sustainability and recyclability outcomes

The European Commission’s packaging waste policy framing highlights that packaging waste is rising and that recycling is difficult and costly, creating pressure for better packaging systems. PPWR is part of that broader policy push to drive innovation and sustainability while reducing packaging waste. For global cosmetics brands, the practical effect is that EU policy direction makes it harder to justify unrecyclable formats—and more valuable to demonstrate credible circularity pathways. Source

Business translation: If your pack design consistently fails recyclability expectations, the future cost is rarely just reputational—it increasingly appears as redesign cycles, disrupted claims, retailer requirements, and compliance exposure.

US direction: packaging EPR is expanding state-by-state (and it changes the economics)

Proskauer’s 2025 guide summarizes how U.S. packaging EPR laws are expanding across states and shifting ongoing obligations to producers, often via Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs). This matters because EPR changes the conversation from “Do we want to be sustainable?” to “We will have to manage, report, and pay for the end-of-life of what we sell.” For cosmetics brands, packaging design becomes an operational variable—affecting reporting burden, compliance complexity, and cost structures over time. Source

Practical takeaway (US): If your packaging is hard to recycle, it can become expensive—not only reputationally, but financially and operationally—because EPR frameworks push end-of-life costs back to the producer.

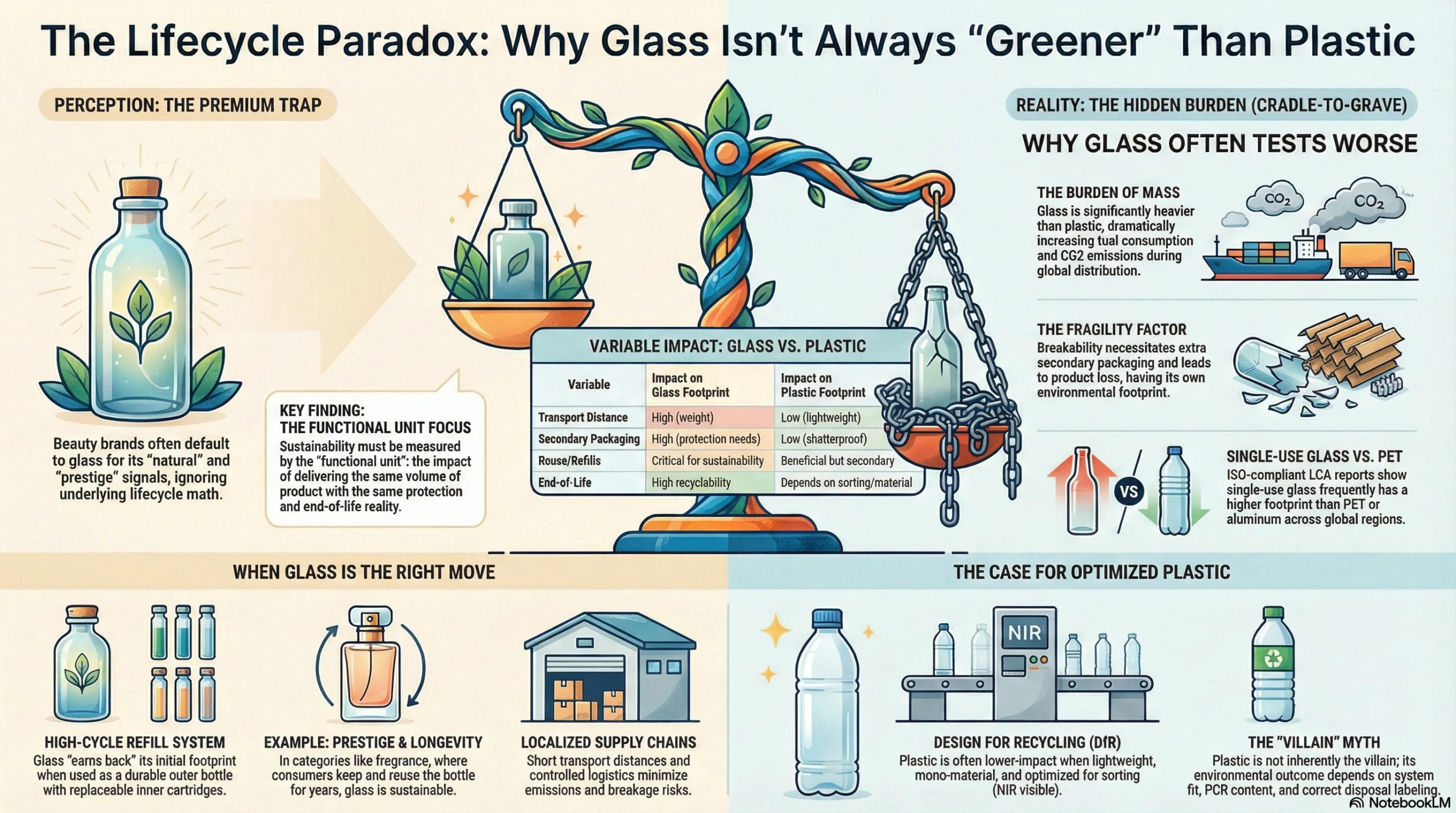

Plastic vs glass: don’t do material swaps without lifecycle thinking

Many beauty teams default to glass because it signals “premium” and “natural” on shelf. But an LCA view forces a different question: Which option creates the lowest impact for the same functional unit (same product volume delivered to the consumer, with the same protection, and the same end‑of‑life reality)? In practice, the answer depends heavily on mass (weight), transport distance, breakage rates, secondary packaging needs, and how many times the container is reused—not simply whether the pack is “plastic” or “glass.”

Why glass can look sustainable—but test worse in cradle‑to‑grave scenarios

Glass has two structural properties that often push its footprint higher in single-use systems:

- It’s heavy, which increases fuel use and emissions in distribution—especially in global cosmetics supply chains that ship from factory → filler → warehouse → retailer → consumer.

- It’s breakable, which can increase protective packaging (corrugated, void fill, dividers), plus product loss (wasted formula has its own footprint).

Those two factors are why “material swapping” without lifecycle math can backfire: you may reduce “plastic feel,” but increase transport and packaging mass.

What the comparative LCA evidence actually says

A comparative LCA report for beverage containers evaluates aluminum, glass, PET, and cartons across multiple regions (USA, Europe, Brazil, India) with ISO 14040/14044-compliant methodology and peer review. Its key finding is directionally consistent: single-use glass frequently shows a higher footprint than PET or aluminum across multiple regions and drink types, while reusable glass can improve—if it achieves enough reuse cycles and the logistics are efficient. Source

Yes, cosmetics is not beverages (different fill lines, viscosity, closures, decorative coatings, and consumer retention). But the report is still a useful caution for cosmetics teams because the physics are the same: mass and transport dominate quickly in many supply chains. The report also explicitly shows that reuse changes outcomes depending on how many refills happen and what the return/cleaning logistics look like—exactly the issue with refillable perfume and skincare bottles.

Practical cosmetics translation: when glass is the right move—and when it’s not

Glass can be a strong choice in cosmetics when it’s paired with a system design that lets it “earn back” its heavier footprint, such as:

- Refillable glass (durable outer bottle + replaceable inner or refill cartridge) where the consumer is likely to refill multiple times.

- Prestige categories where consumers keep the bottle (fragrance) and reuse rates are realistic.

- Local/regional supply chains where transport distances are shorter and breakage risk is controlled.

But glass is not automatically lower impact than a lightweight, DfR‑optimized plastic pack that is:

- designed for sorting (NIR visible, minimal label interference),

- mono-material where feasible,

- includes PCR content,

- correctly labeled for disposal.

That’s why “plastic is the villain” is misleading. The environmental outcome depends on design and system fit, not the headline material.

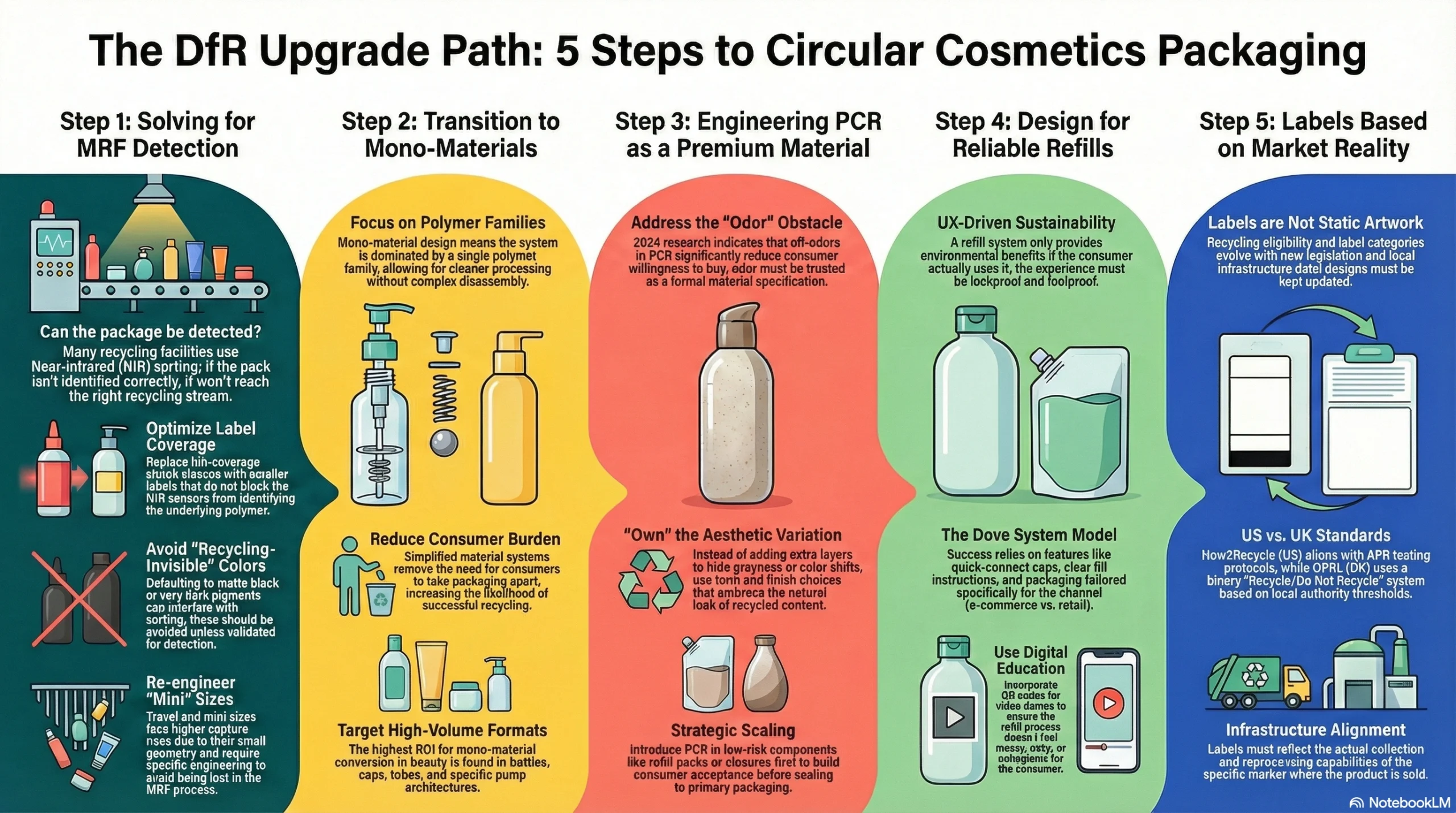

A practical “DfR upgrade path” for cosmetics packaging teams

This is a sequence that works in real packaging development because it follows the actual failure points in the recycling chain. It also prevents teams from jumping to “material swap” as the first move.

Step 1) Start with the MRF reality: can the pack be detected and sorted?

If the pack doesn’t get into the right bale, nothing else matters. Many MRFs use near-infrared (NIR) sorting to identify polymer types. APR’s NIR guidance highlights design features that can interfere with identification and routing: high-coverage shrink sleeves/labels, dark/black colors, and challenging sizes/geometries. Source

Cosmetics-specific fixes to consider:

- Replace full sleeves with lower coverage labels or designs proven not to block NIR detection.

- Avoid defaulting to matte black and very dark pigments unless validated.

- Treat “mini” and travel sizes as a separate engineering problem (capture risk is higher).

Step 2) Move toward mono-material systems where feasible (especially high-volume formats)

Mono-material doesn’t mean “one part.” It means the system is dominated by one polymer family so it can be processed cleanly. Beauty Packaging documents the industry shift toward mono-materials because they simplify recycling and reduce consumer disassembly burden, while noting tooling availability constraints.

Where this is highest ROI in beauty:

- Bottles + caps (large volumes)

- Tubes

- Certain pump architectures (where viable)

Step 3) Engineer PCR like a premium material (odor and aesthetics are not “minor”)

PCR adoption in cosmetics often fails because of sensory and aesthetic variability (odor, color/grayness, consistency). A 2024 study on consumer acceptance of PCR packaging shows that higher PCR content and off-odor can reduce acceptability and willingness to buy; odor pleasantness and familiarity strongly predict consumer judgments. Source

Practical PCR design moves:

- Treat odor as a material spec (not a surprise).

- Use form/finish choices that “own” PCR variation without adding recycling-breaking layers.

- Start PCR where acceptance risk is lower (refill packs, certain closures) and scale upward.

Step 4) Design refill systems like products (UX + education + reliability)

Refill is not sustainable if consumers don’t refill. Successful refills require leakproof, foolproof UX plus education at the moment of use. The Packaging Digest case study on Dove’s system shows why: quick-connect cap, clear fill instructions, QR codes for demos, and packaging engineered differently for e-commerce vs retail.

Cosmetics-specific refill constraints:

- hygiene and contamination control

- seal integrity after repeated cycles

- clear steps so refilling doesn’t feel “messy” or risky

Step 5) Label by market reality (How2Recycle vs OPRL) and keep it updated

Even great DfR design can fail if disposal instructions are wrong. How2Recycle’s guidelines emphasize that eligibility and label categories evolve with legislation and acceptance data, and they align with APR protocols/testing—so you can’t treat recycling labels as static artwork.

In the UK, OPRL is intentionally binary (“Recycle/Do Not Recycle”) based on collection and reprocessing thresholds across local authorities, aligned with ISO principles—so labeling must reflect UK infrastructure reality.

Conclusion: stop blaming plastic—start designing for outcomes

For global cosmetics brands, the sustainability conversation is maturing. The question is no longer “Is it plastic?” It’s:

- Can it be sorted reliably?

- Can it be reprocessed without contaminating PCR?

- Will consumers accept PCR in premium categories where odor and aesthetics matter?

- Will the pack remain compliant as labels and laws evolve?

This is why “plastic is the villain” is the wrong mental model. Plastic is a material family with real advantages (lightweighting, barrier options, durability). The environmental outcome depends on whether the packaging is designed to succeed in the systems we actually have—and the ones regulations are forcing us to build.

FAQs

Not inherently. The environmental outcome depends on whether the packaging is designed for recyclability, can be collected, is accepted and sorted correctly, and has end markets for the recycled resin—an approach reflected in the APR recyclability framework. Source

Cosmetics packs often fail because of design features that interfere with real recycling operations—especially NIR sorting at MRFs. APR explains that high-coverage labels/shrink sleeves, dark colors (including black), and certain geometries can reduce detection and correct sorting, sending otherwise “good” resins to residue or the wrong stream. Source

DfR means engineering the entire pack—bottle/jar, cap, pump, label, inks, adhesives, and any barrier layers—so it can be sorted and reprocessed at scale without degrading yield or PCR quality. APR’s Design Guide evaluates packaging feature-by-feature rather than relying on resin type alone.

Mono-material systems (often polyolefin-based like PP/PE families) can reduce mixed-material contamination and simplify recycling, which is why beauty brands and suppliers are pushing mono-material pumps, tubes, jars, and airless packs—despite tooling availability constraints.

Not always. Refill systems only reduce impact when consumers actually refill repeatedly and the system design makes refilling intuitive, leak-resistant, and hygienic. Dove’s concentrate refill system illustrates how design details (quick-connect cap, clear instructions, QR education) can increase real adoption.

Because labeling reflects different infrastructure and rules. How2Recycle eligibility evolves with legislation and acceptance data and aligns with technical substantiation pathways (including APR protocols), so “Widely Recyclable” status depends on access and real sorting/reprocessing realities. Source

In the UK, OPRL uses a simpler binary approach (“Recycle/Do Not Recycle”) based on how widely local authorities collect and successfully reprocess the packaging type. Source

Not automatically. Lifecycle impact depends on weight, transport, and reuse cycles. A multi-region comparative LCA for beverage containers shows single-use glass often has higher footprints than PET or aluminum in multiple regions, while reuse can change the equation depending on logistics and reuse rates—making it a caution against “material swaps” without lifecycle thinking. Source